At the end of the 20th century there was a lot of anxiety surrounding New Year’s Eve 1999, as a computer bug, which your children or young co-workers have likely never heard of, threatened to cause computer systems around the world to crash. It was known as “Y2K”.

The “millennium bug” was due to a programming oversight in the way computers formatted their internal calendars using a “dd/mm/yy” system that presented a problem when calendars switched from 1999 to the year 2000.

This date change would effectively confuse computers into thinking it was the year 1900 rather than 2000 and could potentially erase or misplace any data or records from the 20th century, and cause systems across multiple industries to glitch and crash.

Luckily, the bug was patched and technological Armageddon never arrived.

So, as the new year approaches once more, read on to discover what we can learn from looking back on the day global markets threatened to crash and how stocks have performed in the years since.

New Year’s Eve 1999 saw the FTSE 100 close at a then record-high

The late 90s were a prosperous time for UK markets and the greater economy as the country bounced back from the downturn of the early 90s and saw significant growth across multiple sectors.

As celebrants counted down the seconds to the new millennium on New Year’s Eve 1999, the FTSE 100, the UK’s leading stock market index, closed at what was then a record high of 6,930.

It was a record that stood for almost 15 years until it was surpassed in February 2015.

Any lingering concerns about the Y2K bug, were far outweighed by investors confidence in the “dot-com” boom of the late 90s and early 2000s as the rapid progress of the internet, technology firms, and online retail brought a whole new sector of business for investments.

In the intervening years, there was at first the bursting of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s, and then the global financial crisis in 2008 that saw billions in losses and from which markets took years to recover.

In more recent years, macroeconomic events such as Brexit, the pandemic, the energy crisis, and war in Ukraine, have all threatened to cause volatility across markets.

So, it might shock you to learn that despite all that turmoil and turbulence over the proceeding 20 years, the FTSE 100 barely moved, and in fact actually increased over time.

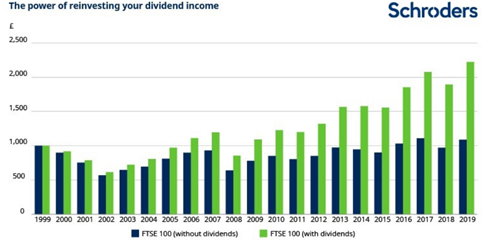

The FTSE 100 produced average annual returns of 0.4%, or 4% with dividends reinvested, between 1999 and 2019

As of 31 December 2019, the index stood at 7,542, about 600 points higher than in 1999, which according to Schroders works out as an average annual return of 0.4%.

They go on to report that the figure is closer to 4% when dividends are reinvested over the period, or a 122% return for the 20 years between 1999 and 2019.

Source: Schroders

This effectively means that if you had £1,000 invested in the FTSE 100 on 31 December 1999 and kept the investment, reinvesting the dividends, it would be worth £2,222 today (before adjusting for inflation and associated fees).

While stock markets can see downturns and sharp dips, just as they did when the dot-com bubble burst or the 2008 financial crisis hit, over long-term periods of 5, 10, or 20 years they typically see positive returns for investors.

Consider the peaks and troughs of the FTSE 100 between 31 December 1999 and 9 December 2022 as shown by the graph below:

Source: London Stock Exchange

It is apparent that, while the stock market can see big downturns in the short term when investors panic — as they could have done if Y2K had come to pass — over longer periods it tends to rebound and eventually grow.

According to a study by IG, for any 10-year period between 1984 and 2019, UK investors would, on average, have seen annual returns of 8.43% with dividends reinvested.

Patience is key and its vital that you don’t let short-term instability influence your investing decisions and potentially lock in a loss before the investment has a chance to rebound and recover.

Avoid short-term mistakes, while taking a long-term view of your investments

It can be easy to let emotions influence your decision-making. The theory of “loss aversion” posits that human beings feel the pain of losses twice as much as the pleasure of gains.

Emotional decisions, driven by psychological biases, can hinder your progress towards long-term goals. Working with a financial planner can be especially beneficial here as we can act as a sounding board to reassure you that you’re making the correct choices.

It is important to avoid making investing mistakes such as:

- Not having a clear plan of your long-term objectives and how your investments play into those aims

- Taking too much or too little risk as high-risk investments carry the burden of the potential for losses, while too-safe investments might not generate significant enough returns

- Not diversifying enough to protect your overall portfolio against dips in localised markets or in certain stocks or commodities

- Investing before setting aside emergency savings to cover key bills such as rent, utilities, and groceries.

One way to ensure your portfolio is structured in the right way for you is to seek professional advice.

Research from the International Longevity Centre discovered that clients who took professional financial advice between 2001 and 2006 had, on average, £47,706 more wealth by 2014/16 than individuals who had not taken advice in the first place.

Get in touch

If you would like to know more about developing an investment plan that matches your long-term needs and tolerance for risk, contact us by emailing info@lloydosullivan.co.uk or calling 020 8941 9779.

Please note:

This article is no substitute for financial advice and should not be treated as such. To determine the best course of action for your individual circumstances, please contact us.

The value of your investments (and any income from them) can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investments should be considered over the longer term and should fit in with your overall attitude to risk and financial circumstances.

Production

Production